|

mandaotry reportin in Australia

|

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE AUSTRALIAN DATA ON MANDATORY

REPORTING OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE?

- Pat Yudkin

Summary

To attempt to gain some insight into the possible effects of mandatory reporting

of child sexual abuse (CSA) I investigated data from Australia. Of the eight

states and territories of Australia, seven had mandatory reporting of CSA in

place before 2005. Western Australia introduced mandatory reporting of CSA in

January 2009. I hypothesized that there would be a rise in identified cases of

CSA in Western Australia after 2009 that was not matched by rises in the other

jurisdictions.

I examined trends in the incidence of substantiated CSA over the eight years

2006-07 to 2013-14. I found the expected rise in cases of CSA in Western

Australia, but this was matched by comparable rises in other jurisdictions,

notably New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. Further, throughout the

period, New South Wales showed an unusually high incidence of CSA compared with

the other jurisdictions.

There is wide variation, both across jurisdictions and over time, in the

substance of the mandatory reporting laws relating to CSA. Similar variation

exists in the interpretation and implementation of these laws in practice, the

organization of child protection services and the resources available. For all

these reasons, routinely collected data needs careful and painstaking

interpretation. It is simplistic to assume that such data can be used to assess

the impact of a single legal change.

Comparisons between jurisdictions, between countries, and across time periods in

the same jurisdiction, using routinely collected data, will not have a simple

interpretation.

METHOD

To attempt to gain some insight into the possible effects of mandatory reporting

of CSA, I investigated data from Australia. I used Australian day for several

reasons. First, detailed data on CSA is published annually in the reports “Child

Protection Australia” from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (1).

All these reports are available online. Second, a number of influential papers

on mandatory reporting of CSA in Australia have been published by Professor Ben

Mathews of Queensland University of Technology. Extracts from papers by

Professor Mathews have been used in support of mandatory reporting of CSA on the

website of the pressure group Mandate Now (2).

Of the eight states and territories in Australia, seven had mandatory reporting

of CSA in place before 2005. The eighth, Western Australia, introduced mandatory

reporting for CSA on 1st January 2009. I examined data on CSA in Australia over

the period 2006-2013. I hypothesized that there would be a rise in identified

cases of CSA in Western Australia after 2009 that was not matched by rises in

the other jurisdictions.

Source of data

The two main sources used were the report by Professor Mathews for the Royal

Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 'Mandatory

Reporting Laws for Child Sexual Abuse in Australia: a Legislative History' (3),

and the annual reports “Child Protection Australia”, from the Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare (1). I covered the eight-year period 2006-07 to

2013-14, avoiding data from earlier years because, for Victoria, the earlier

data is not consistent with that from 2006-07 onwards (4). The data relates to

children aged 0 to 17 years throughout.

Mandatory reporting of CSA: differences in legal requirements across the eight

Australian jurisdictions

The report for the Royal Commission (3) highlights the many differences between

jurisdictions in the history and present day situation of the mandatory

reporting laws, summarised below.

When was mandated reporting of CSA introduced?

Mandatory reporting laws specifically for CSA were introduced as follows:

Northern Territories INT) 1984; Tasmania (Tas) 1987; New South Wales (NSW) 1988;

Victoria (Vic) 1993; South Australia (SA) 1994; Australian Capital Territory

(ACT) 19979 Queensland (Qld) 2004; Western Australia (WA) 2009. All

jurisdictions except WA also require mandatory reporting of other forms of child

abuse and neglect.

Over time, changes in legislation have occurred in all jurisdictions. At the

time of the royal Commission Report (August 2014) the legal requirements with

respect to CSA were as follows.

Who is mandated to report?

Teachers, doctors, nurses and the police are mandated reporters in all

jurisdictions except Qld, which mandates only doctors, nurses and teachers. WA

and Vic also include midwives. ACT and NSW include, in addition, a wide range of

paid professionals. SA and Tas go further in also mandating some volunteers. In

NT all citizens are mandated to report.

Apart from NT, SA is the only jurisdiction to include ministers of religion and

other workers in religious organizations (paid or voluntary), as mandated

reporters. Notably, a minister of religion is not required to divulge

information communicated in the course of a religious confession.

What is the definition of a child?

The reporting duty relates to children under the age of 18, except in NSW (under

16) and Victoria (under 17).

What level of sexual abuse must be reported?

It is mandatory to report all sexual abuse in ACT, NT, SA, Tas and WA. In NSW

and Vic, the child must be eat risk of ‘significant harm'. Qld has a dual

requirement: for doctors and nurses, there must be a risk of ‘significant harm',

but school staff are required to report all sexual abuse.

What time period does the abuse relate to?

Past or ongoing abuse must be reported in ACT and WA. In SA and Tas, the

likelihood of future abuse must also be reported if this relates to a person

residing with the child. In NSW, NT, Qld and Vic, it is mandatory to report the

likelihood of future abuse as well as past and ongoing abuse.

How certain of abuse does the reporter have to be?

There are differences in the site of mind that a reporter must have before the

duty is activated. Some legislation uses the criterion of ‘belief on reasonable

grounds' (ACT, NT, Vic, WA) and some the criterion of ‘suspects on reasonable

grounds' (NSW, Qld, SA, Tas). Belief requires a higher level of certainty than

suspicion.

What are the penalties for non-reporting?

Since 2010 there has been no penalty in NSW. In NT, Qld, SA, Tas, Vic and WA,

there are fines for non-reporting, ranging from $1,408 in Vic to $26,000 in NT.

In ACT, there is a fine of $5,500, imprisonment of up to 6 months, or both.

Information available on CSA from annual reports ‘Child Protection Australia’

Notifications. investigations and substantiations of

CSA

The Child Protection reports are detailed and comprehensive, and cover many

aspects of child protection. They refer to the numbers of ‘notifications’,

‘investigations’ and ‘substantiations' of child abuse. In all jurisdictions, not

all notifications of abuse will be investigated, and of those investigated, only

a proportion will be found to be substantiations, i.e. to meet the criteria for

child abuse. The criteria for recording an event as a ‘notification',

‘investigation’ or ‘substantiation’ vary across jurisdictions.

In practice, the numbers of these events depends not only on the legal

requirements, but also on factors such as how the law is interpreted, the

organization and efficiency of child protection services in each jurisdiction,

the resources available, etc.

Most of the published tables combine all forms of child abuse, i.e. physical

abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect. The reports do not include the

number of notifications or investigations specifically of USA. Neither do they

present information about the people making the notifications of CSA,

particularly whether or not they were mandated reporters.

For CSA alone, the reports record only the number of substantiated cases and the

number of children in substantiations (a child may be the subject of more than

one substantiated case.) The year runs from 1st July to 30th June.

An eight-year study of substantiations of child sexual abuse across the states

and territories of Australia

Results

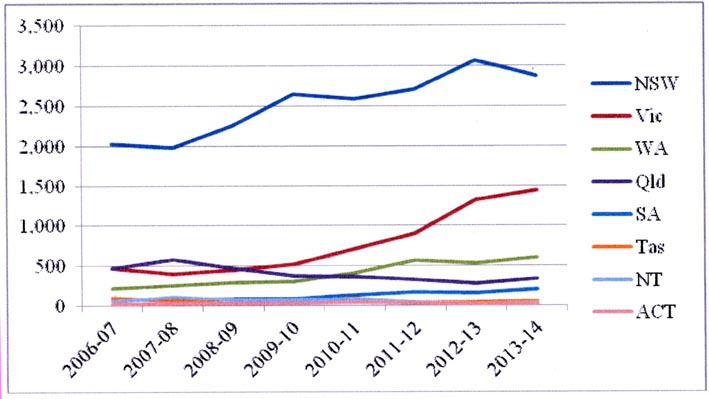

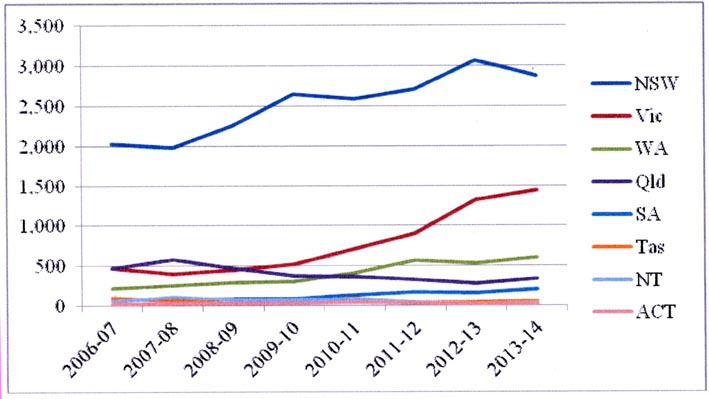

Figure 1 shows, first, that the number of children in substantiations of sexual

abuse in New South Wales (NSW) was much higher than in any other jurisdiction.

Secondly, numbers rose throughout the period in New South Wales, Victoria (Vic),

Western Australia (WA) and South Australia (SA), and fell in Queensland (Qld).

Thirdly, numbers in Tasmania (Tas), Northern Territory (NT) and Australian

Capital Territories (ACT) were very small compared with other jurisdictions.

Table1.

Numbers of children in substantiations of child sexual abuse across the states

and territories of Australia.

The variation in numbers can partly be attributed to population size. New South

Wales has the largest population of all the jurisdictions, followed by Victoria,

Queensland and Western Australia.

And over the eight-year period, the population grew in all jurisdictions except

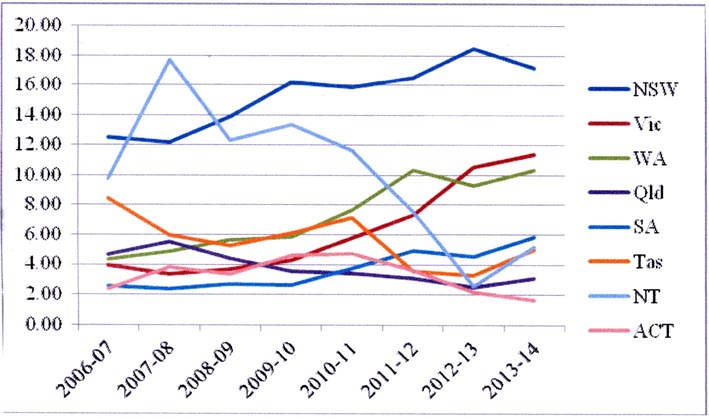

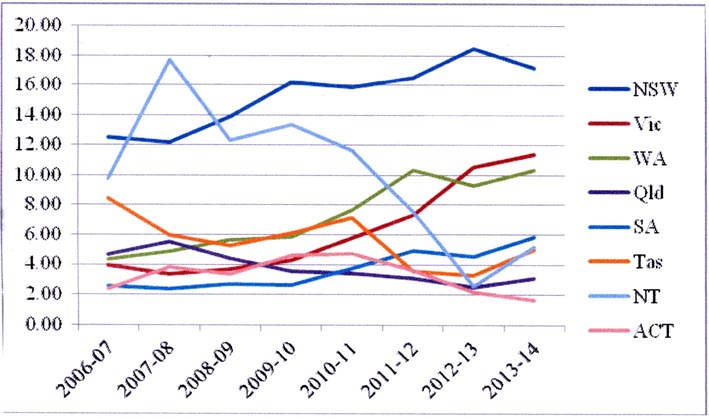

Tasmania. Figure 2 shows, for each jurisdiction, the numbers of children in

substantiations of sexual abuse per 10,000 children aged 0-17 in the population.

Table 2 Children in substantiations of sexual abuse: incidence per 10,000

children

After adjustment for population size, New South Wales remained an outlier, but

the incidence of child sexual abuse in the smallest jurisdictions and in South

Australia was no longer overshadowed.

The volatility in Northern Territory is difficult to interpret without further

information. The peak in 2007-08 represents 110 abused children; the trough in

2012-13 only 16. The incidence of CSA in Tasmania fell over the period and that

in the Australian Capital Territories rose and then fell back.

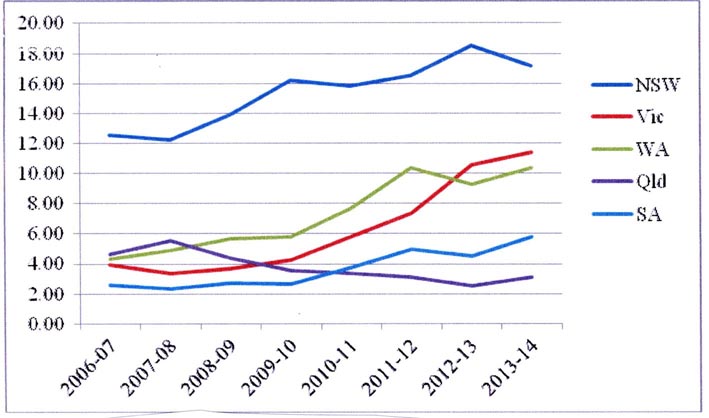

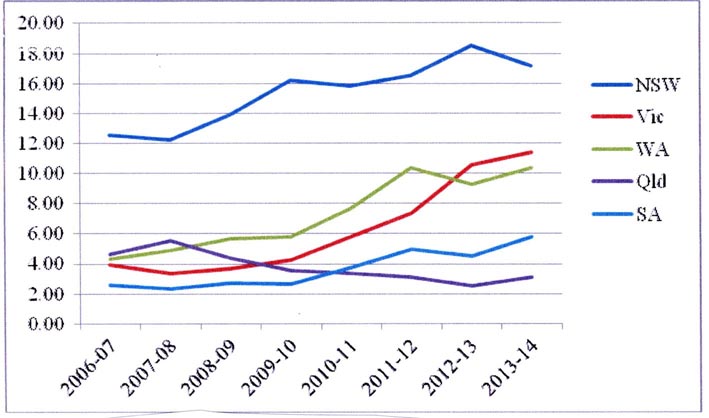

Removing the three smallest jurisdictions from the figure produces a clearer

picture in the larger states. The experience of Western Australia, where

mandatory reporting of CSA was introduced in 2009, is of particular interest.

Table 3 Children in substantiations of sexual abuse: incidence per 10,000 five

states

Throughout the period, the incidence of substantiated CSA in New South Wales was

considerably higher than in any of the other four jurisdictions. The incidence

of substantiated CSA rose over the eight-year period in New South Wales,

Victoria Western Australia and South Australia. There was a fall in the

incidence of substantiated CSA in Queensland.

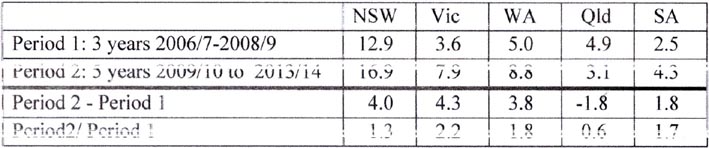

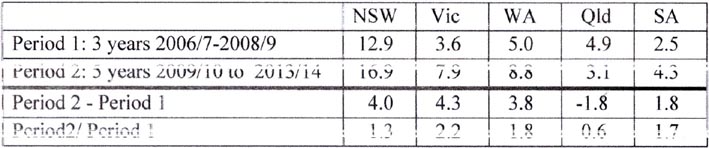

As Western Australia introduced mandatory reporting in January 2009, I compared

the three years 2006-07 to 2008-09 with the five years 2009-10 to 2013-14. (The

first six months of 2009 would fall in the first period, and the second six

months in the second period.)

Table 4 Children in substantiations of CSA per 10,000 children, average

incidence per year

Between the two periods the average incidence of children in substantiated cases

of CSA in Western Australia increased from 5.0 per 10,000 to 8.8 per 10,000, an

absolute rise of 3.8 per 10,000. As Table 4 shows, greater absolute rises

occurred in New South Wales (4.0 per 10,000) and Victoria (4.3 per 10,000). In

relative terms the incidence rose 1.8 times in Western Australia, while the

incidence more than doubled in Victoria and rose 1.7 times in South Australia.

I considered whether the increases in identified cases of CSA in New South

Wales, Victoria and South Australia and the fall in Queensland could be related

to changes in their mandatory reporting laws in the eight-year period.

In New South Wales three legal changes occurred, all in 2010. These were the

introduction of ‘significant harm' (instead of ‘harm’) to activate a reporting

duty, the removal of a penalty for non- compliance with the law, and the

enabling of reports to be made to child wellbeing units. The first two of these

changes might be expected to decrease reports (and therefore substantiations) of

CSA, rather than increase them.

In Victoria there were two key legal changes in the period. In 2007 came a

clarification that ‘harm’ can be caused by a single act or omission, as well as

a series of acts and omissions. And in 2010 midwives were added as a mandated

reporter group. In SA in 2006, three additional groups were added to the list of

mandated reporters. They were ministers of religion, employees and volunteers in

religious organizations, and employees and volunteers in sporting or

recreational organizations.

These changes in Victoria and South Australia might be expected to have a

positive impact on reports of CSA, and thus on substantiations of CSA.

One key change in the law occurred in Queensland in 2012, when teachers were

required to report all cases of CSA and suspected cases of future CSA. This

change was too late to affect the observed fall in CSA incidence and in any case

would be expected to work in the opposite direction.

Discussion

There are marked variations across the states and territories of Australia in

many aspects of their mandatory reporting laws. The law were introduced at

different times, the earliest in 1984 (Northern Territory), the most recent in

2009 (Western Australia).

Differences are seen in the range of people mandated to report, the level of

abuse to be reported, the degree of belief that abuse has occurred (or may occur

in future), and the penalty for non-adherence.

There are differences between jurisdictions too in the interpretation and

implementation of the laws, the organization of child protection services and

the resources available. All these aspects vary not only across jurisdictions

but also over time.

In view of the high-profile cases of CSA in religious settings, it is notable

that ministers of religion and other workers in religious organizations (paid or

voluntary) are mandated reporters only in Northern Territory (where all citizens

are mandated reporters) and South Australia. In South Australia a minister of

religion is not required to divulge information communicated in the course of a

religious confession.

The current range of penalties for breaking the law is very wide, ranging from a

fine of up to $26,000 (Northern Territory) to no penalty at all (New South

Wales).

An examination of substantiated cases of CSA over the period 2006-07 to 2013-14

produced two main findings.

First, the incidence of CSA was consistently higher in New South Wales than in

any otherjuris diction.

Second, as expected, there was a rise in the incidence of CSA in Western

Australia where mandatory reporting was introduced in 2009. The rise occurred

throughout the period, but was more rapid after 2009 than before.

This would be consistent with an effect of mandatory reporting. However, as

similar rises in the incidence of CSA occurred in Victoria, New South Wales and

South Australia, where there were no major legal changes, it is clear that other

factors were in play. It would be simplistic to assume that the introduction of

mandatory reporting was responsible for the increase in substantiated CSA in

Western Australia.

Mathews et al. made this clear in their 2015 presentation to the Australasian

Conference on Child Abuse and Neglect (5). They pointed out that while

introducing a new legal duty can increase reports and substantiations of CSA,

these outcomes can also be influenced by non-legal contextual factors, such as

financial resources, personnel, child protection policy, and political pressure.

In general, the use of routinely collected data to provide information on the

working of a mandatory reporting law is fraught with difficulties. Comparisons

between jurisdictions, between countries, and across time periods in the same

jurisdiction, using routinely collected data, will not have a simple

interpretation.

References

1 . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2008. Child protection Australia

2006-07. Child welfare series no. 43. Cat. no. CWS 31. Canberra: AIHW; annually

to Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015.

Child protection Australia: 2013-14. Child Welfare series no. 61. Cat. no. CWS

52. Canberra: AIHW.

2. Mandate Now website: mandatenow.org.uk

3. Mathews B. (2014a). Mandatory Reporting Laws for Child Sexual Abuse in

Australia: a Legislative History, written for the Royal Commission into

Institutional Responses to Child Sexual able, Sydney.

ISBN 978-1-925118:5 7-5 (Print); ISBN 978-1-9251 18-58-2 (Online) 4. Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare 2009. Child protection Australia 2007-08. Child

welfare series n0.45 Cat. no. CWS 33. Canberra: MHW. Put 5. Mathews B, Bromfield

L, Walsh K, Vimpani G, Coe S. Mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse: 10 year

trends from a national study across reporter groups and different legal

frameworks. Presentation to Australasian Conference on Child Abuse and Neglect

(ACCAN), Auckland, 2015

Acknowledgement

1 am grateful to Professor Ben Mathews for bringing a number of helpful papers

to my attention and for sharing his expertise on this subject.

A note on the limitations of the data

The annual reports from the Australian Institute of Hea1th and Welfare (AIHW)

are based on the financial year July 1st to June 30th. Reported substantiations

relate only to substantiations of investigations started in the year and

completed by August 31st. Substantiations of uncompleted investigations are

never reported.

Based on the published data, it is difficult to determine whether or not this is

a serious issue. The proportion of uncompleted investigations of CSA is not

published. However, this information is available for all types of child abuse,

and it shows wide variation across jurisdictions.

Two jurisdictions of interest in this paper are New South Wales and Victoria. In

relation to all forms of child abuse, both had consistently good records over

the period 2006-07 to 2013-14. New South Wales completed over 95% of

investigations every year. Victoria completed well over 90% of investigations in

seven of the eight years (and 89% in the other year). The record in other

jurisdictions was more variable.

A comparison of the data published in the AIHW reports with that in a paper by

Professor Mathews (Mathews B (2014b). Mandatory reporting Laws and

Identification of Child Abuse and neglect: consideration of different

maltreatment types and a cross-jurisdictional analysis of child sexual abuse

reports.

Soc. Sci. 2014, 3:460-482. doi:10.3390/socsci303460) shows some quite large

differences. Professor Mathews used day provided directly by child protection

agencies in the various Australian states and territories. The annual number of

substantiations reported by Mathews was therefore not limited to substantiations

based on investigations started and completed during the year, as is the AIHW

data. Further investigation is needed to know whether this is the explanation

for the differences found but it is unlikely to affect the main thrust of my

conclusions.

|

Press back button on browser to return to the

HOME PAGE

| |